2 ways to activate Windows 10 for FREE without additional software

As you know, Microsoft notified Windows 10 is “the last version of Windows” and explained that they will be focused on the development of powerful and new features under the guise of software updates instead of building a new version. This means there will be no Windows 10.1 or 11 in the future(*). So if you are thinking about an upgrade, this is the best time to get it.

(*) New update: An expected release of version 11 was launched in late 2021. Read this post for more information.

Windows 10 free upgrade

The representative of Microsoft has confirmed that Windows 10 is a free upgrade for all customers using a genuine copy of Windows 7 or higher. But this offer officially will expire on Friday so do not hesitate to own it before it is too late. Your time is running out. After July 29, the upgrade will cost up to $119 for the Home edition or $199 for the Professional one. Personally, that amount of money is enough to pay my rent this month so there is no reason for me to deny that.

Should you upgrade to Windows 10

“Do not upgrade to Windows 10”. This seems to contradict the above analysis but that is the statement of security experts. They said that Microsoft has been violating users’ privacy by collecting their personal information like gender, age, hobby, and Internet habits… without your permission. The options relating to sending feedback and data to Microsoft were enabled automatically from the moment that you installed Windows 10 successfully so most people don’t know about them. However, you can disable them in Settings/Privacy easily.

Install Windows 10 using ISO file instead of an upgrade

You can get the latest version of Windows 10 Professional here if you don’t have it already. If you have ever installed any versions of Windows before, I am sure you will have no difficulty getting started with Windows 10. If you are looking to install it with a USB flash drive, please search for “how to install Windows 10 from a bootable USB stick”. There are many detailed instructions for installing Windows 10 on the web.

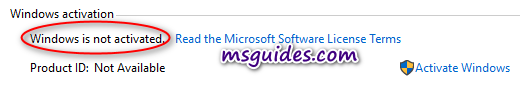

Activate Windows 10 without using any software

If you are using another version of Windows, please navigate to the Windows OS category and select a suitable article.

Method 1: Manual activation

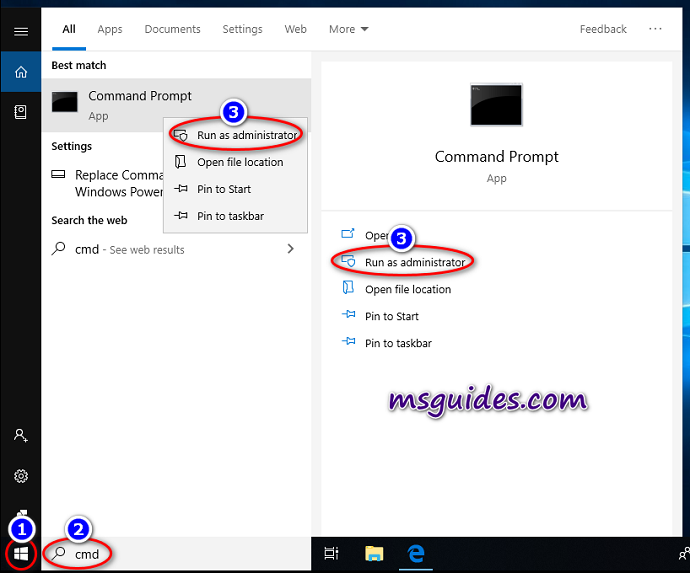

Step 1.1: Open Command Prompt as administrator.

Click on the start button, search for “cmd” then run it with administrator rights.

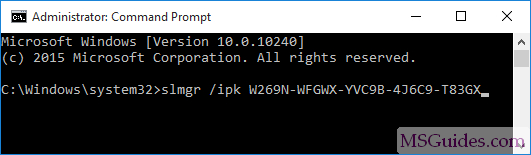

Step 1.2: Install KMS client key.

Use the command “slmgr /ipk yourlicensekey” to install a license key (yourlicensekey is the activation key that corresponds to your Windows edition). The following is the list of Windows 10 Volume license keys.

Home: TX9XD-98N7V-6WMQ6-BX7FG-H8Q99

Home N: 3KHY7-WNT83-DGQKR-F7HPR-844BM

Home Single Language: 7HNRX-D7KGG-3K4RQ-4WPJ4-YTDFH

Home Country Specific: PVMJN-6DFY6-9CCP6-7BKTT-D3WVR

Professional: W269N-WFGWX-YVC9B-4J6C9-T83GX

Professional N: MH37W-N47XK-V7XM9-C7227-GCQG9

Education: NW6C2-QMPVW-D7KKK-3GKT6-VCFB2

Education N: 2WH4N-8QGBV-H22JP-CT43Q-MDWWJ

Enterprise: NPPR9-FWDCX-D2C8J-H872K-2YT43

Enterprise N: DPH2V-TTNVB-4X9Q3-TJR4H-KHJW4

Note: You need to hit [Enter] key to execute commands.

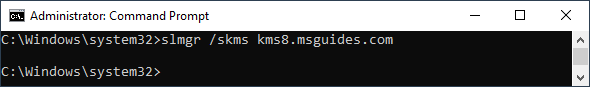

Step 1.3: Set KMS machine address.

Use the command “slmgr /skms kms8.msguides.com” to connect to my KMS server.

Step 1.4: Activate your Windows.

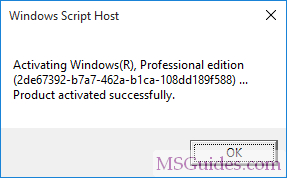

The last step is to activate your Windows using the command “slmgr /ato”.

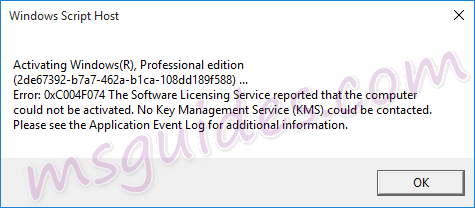

If you see the error 0xC004F074, it means that your internet connection is unstable or the server is busy. Please make sure your device is online and try the command “ato” again until you succeed.

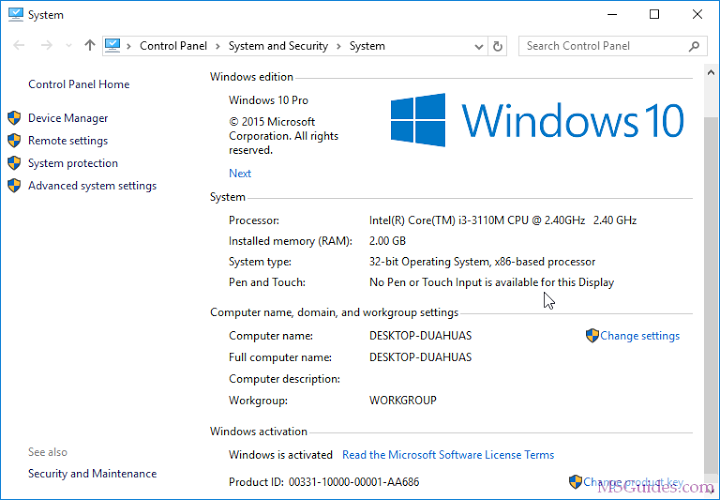

Now check the activation status again.

Method 2: Using a batch file

This one is not recommended anymore due to the new update of Microsoft.

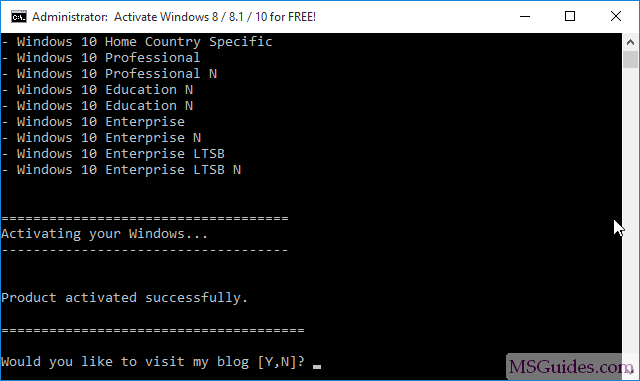

Step 2.1: Copy the code below into a new text document.

@echo off

title Activate Windows 10 (ALL versions) for FREE - MSGuides.com&cls&echo =====================================================================================&echo #Project: Activating Microsoft software products for FREE without additional software&echo =====================================================================================&echo.&echo #Supported products:&echo - Windows 10 Home&echo - Windows 10 Professional&echo - Windows 10 Education&echo - Windows 10 Enterprise&echo.&echo.&echo ============================================================================&echo Activating your Windows...&cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ckms >nul&cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /upk >nul&cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /cpky >nul&set i=1&wmic os | findstr /I "enterprise" >nul

if %errorlevel% EQU 0 (cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk NPPR9-FWDCX-D2C8J-H872K-2YT43 >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk DPH2V-TTNVB-4X9Q3-TJR4H-KHJW4 >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk YYVX9-NTFWV-6MDM3-9PT4T-4M68B >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk 44RPN-FTY23-9VTTB-MP9BX-T84FV >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk WNMTR-4C88C-JK8YV-HQ7T2-76DF9 >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk 2F77B-TNFGY-69QQF-B8YKP-D69TJ >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk DCPHK-NFMTC-H88MJ-PFHPY-QJ4BJ >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk QFFDN-GRT3P-VKWWX-X7T3R-8B639 >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk M7XTQ-FN8P6-TTKYV-9D4CC-J462D >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk 92NFX-8DJQP-P6BBQ-THF9C-7CG2H >nul&goto skms) else wmic os | findstr /I "home" >nul

if %errorlevel% EQU 0 (cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk TX9XD-98N7V-6WMQ6-BX7FG-H8Q99 >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk 3KHY7-WNT83-DGQKR-F7HPR-844BM >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk 7HNRX-D7KGG-3K4RQ-4WPJ4-YTDFH >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk PVMJN-6DFY6-9CCP6-7BKTT-D3WVR >nul&goto skms) else wmic os | findstr /I "education" >nul

if %errorlevel% EQU 0 (cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk NW6C2-QMPVW-D7KKK-3GKT6-VCFB2 >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk 2WH4N-8QGBV-H22JP-CT43Q-MDWWJ >nul&goto skms) else wmic os | findstr /I "10 pro" >nul

if %errorlevel% EQU 0 (cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk W269N-WFGWX-YVC9B-4J6C9-T83GX >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk MH37W-N47XK-V7XM9-C7227-GCQG9 >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk NRG8B-VKK3Q-CXVCJ-9G2XF-6Q84J >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk 9FNHH-K3HBT-3W4TD-6383H-6XYWF >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk 6TP4R-GNPTD-KYYHQ-7B7DP-J447Y >nul||cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ipk YVWGF-BXNMC-HTQYQ-CPQ99-66QFC >nul&goto skms) else (goto notsupported)

:skms

if %i% GTR 10 goto busy

if %i% EQU 1 set KMS=kms7.MSGuides.com

if %i% EQU 2 set KMS=kms8.MSGuides.com

if %i% EQU 3 set KMS=kms9.MSGuides.com

if %i% GTR 3 goto ato

cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /skms %KMS%:1688 >nul

:ato

echo ============================================================================&echo.&echo.&cscript //nologo slmgr.vbs /ato | find /i "successfully" && (echo.&echo ============================================================================&echo.&echo #My official blog: MSGuides.com&echo.&echo #How it works: bit.ly/kms-server&echo.&echo #Please feel free to contact me at [email protected] if you have any questions or concerns.&echo.&echo #Please consider supporting this project: donate.msguides.com&echo #Your support is helping me keep my servers running 24/7!&echo.&echo ============================================================================&choice /n /c YN /m "Would you like to visit my blog [Y,N]?" & if errorlevel 2 exit) || (echo The connection to my KMS server failed! Trying to connect to another one... & echo Please wait... & echo. & echo. & set /a i+=1 & goto skms)

explorer "http://MSGuides.com"&goto halt

:notsupported

echo ============================================================================&echo.&echo Sorry, your version is not supported.&echo.&goto halt

:busy

echo ============================================================================&echo.&echo Sorry, the server is busy and can't respond to your request. Please try again.&echo.

:halt

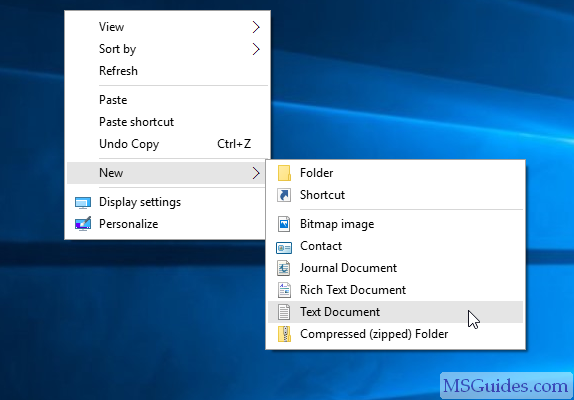

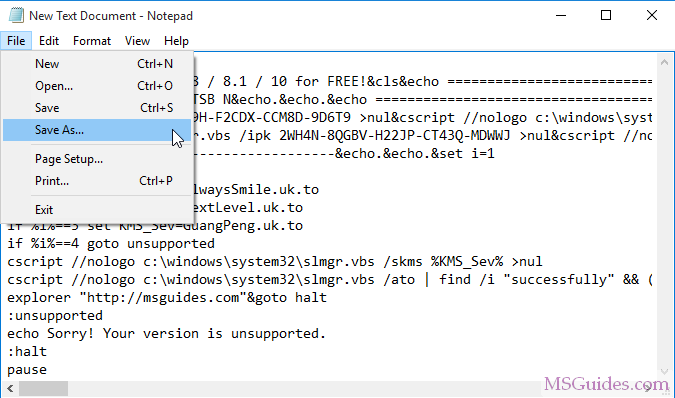

pause >nulCreate a new text document.

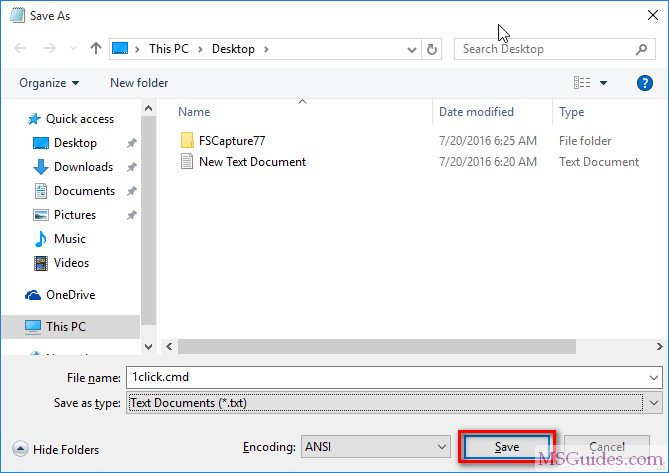

Step 2.2: Paste the code into the text file. Then save it as a batch file (named “1click.cmd”).

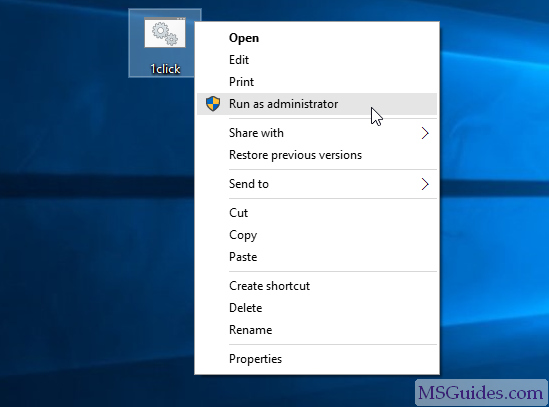

Step 2.3: Run the batch file as administrator.

Please wait a minute.

Note: If you guys see three times the same error message saying that the connection to the KMS server was unsuccessful, please read this post.

Check the activation status again.

If you would have any questions or concerns, please leave your comments. I would be glad to explain in more details. Thank you so much for all your feedback and support!

Wow, works great

Thank you so much

thank you so much

thank you very much

Nice. Its working perfectly.

It’s working, but i prefer legit keys from h y p e st key

great tutorial! super helpful!

thank you very much

thank you! method 1 was successful its working again.

Its been prompting that serve is busy since last 6 months!

Thank you very much it’s working .My G*d 🙏🙏 bless you

It’s working! Thousand of thanks!

Mr Guang,I need your attention and help sir ,either of the method is working, having this in red notice, we can’t activate window on this device as we can’t connect to your organization activation server .make sure you are connected to the organizations network and try again. If you continue having problem with activation contact organization support person

Error code:0xC004F074

Please sir what can we do to this!!!

OH HOLY IT WORKS!! THANK YOU SO MUCH 😀

The first method worked for me, thanks.

It Worked like a charm, I was a bit doubtful at first.

Thanks.

Worked for me on Win 10 Pro. Thank you very much!

i got an error server execution failed, 0x80080005 swbemobjectx, Anyone knows why and what can i do?

This method is the way to go. Don’t waste your money on keys from third party sites. I used one and in just 2 months time I got an error stating that windows is no longer activated and the product key is invalid.

Thank you for appeared in my Google search, it’s successfully worked in my Win 10 Pro

This worked for me on Windows 10 Pro. Thank you!

Method 1 works like a charm! Thank you

THE METHOD 1 IS WORKING FOR ME FOR ALMOST 5 YEARS, BUT NOW THE METHOD 1 IS NOT WORKING, CAN YOU PLEASE HELP ME SIR?

still works. 🙂

Method 1 worked wonderfully thx

I would really like to thank you. As your help worked. Thank you again and thank you very much. Thank you.

I love you mr mike pence vice president of uganda